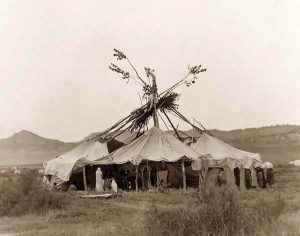

David Carson’s Notes from Turtle Island are a series of blog posts introducing the north American continent as it was known by the ancient indigenous people who lived there.

Let’s begin at the beginning.

First there was the rock and it was floating in the void. The Great Spirit, the First Thought, blew his breath on the rock and the rock became heated and molten. Ice, frozen water came together with the rock and created an electrical charge. Snaking electricity enveloped the rock and Thunder Birds were born from this union.

Lightening streamed from the fierce eyes of these great thunder beings and their beating wings brought storms. The steaming water created the sheltering sky, the atmosphere, space. Ash from the rock became the earth and the soil covering the earth. Great Spirit then took elements from each of the creations, pressed them together into a ball and the sun was born. Then the moon was formed as a companion to reflect the sun. These are said to be our relatives, our first relations. We are related to fire, air, earth and water, the sun, moon and stars and all celestial phenomenon.

The Great Spirit gazed upon the ball of mud that was to be our mother planet. Again, he blew his breath, this time on the mud covering our globe. Plants began to grow, trees and countless other living beings emerged from the mud: all the animals, the flora, every life form including humans, was created from the mud and breath from the Maker of Life.

When we see a beautiful sunset, a far off mountain peak, a placid lake or a rushing river or sit next to a warm fire, it harkens back to the infancy of creation and the wonder of the gift of being.

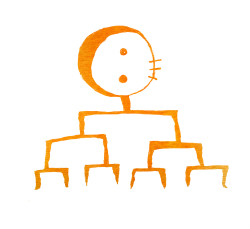

When one acknowledges their human relations, one might begin with immediate family, one’s parents and their offspring. We stand at the top of a pyramid. Below that, are our parent’s parents. And below them are our parent’s parent’s parents and so on. We stand on the shoulders of countless ancestors. The math will soon show that we have more relatives than we can possibly keep track of and that our lineage is incalculable going all the way back to the primal mud.

The term all my relations is one heard often in Native America today. The term expresses well the ecological community of which we are a part. It is a prayer, a litany of kindness, a commitment to a responsibility for the well-being of future generations so that the tree of life will not wither and die.

Relations, relationships, relatives, these are at the heart of Native America. All my relations are often the last words heard closing off a ceremony. As human beings we are a composite of relationships, first with ourselves and then extending to all living beings: to our greater family, to the earth, advancing even further to the star nations and all of creation. It is a sure knowledge that when we harm others, animals or our planet, we harm ourselves and when we diminish others we diminish ourselves.

Now, in this time of the world all my relations is a good concept to remember. We are all one.

David Carson was raised in Oklahoma Indian Country and is of Choctaw descent. He is the author of How to find your spirit Animal, Crossing into Medicine Country: A Journey into Native American Healing and is co-creator of the bestselling Medicine Cards: The Discovery of Power through the Ways of the Animals, which explains how to receive guidance from animals. See David Carson interview.

David Carson was raised in Oklahoma Indian Country and is of Choctaw descent. He is the author of How to find your spirit Animal, Crossing into Medicine Country: A Journey into Native American Healing and is co-creator of the bestselling Medicine Cards: The Discovery of Power through the Ways of the Animals, which explains how to receive guidance from animals. See David Carson interview.

You can contact David Carson via e-mail at makingmedicine@gmail.com.

Animal, Crossing into Medicine Country: A Journey into Native American Healing and is co-creator of the bestselling Medicine Cards: The Discovery of Power through the Ways of the Animals, which explains how to receive guidance from animals. Last week we phoned David in New Mexico and asked him some questions for our Watkins Wisdom interview series.

Animal, Crossing into Medicine Country: A Journey into Native American Healing and is co-creator of the bestselling Medicine Cards: The Discovery of Power through the Ways of the Animals, which explains how to receive guidance from animals. Last week we phoned David in New Mexico and asked him some questions for our Watkins Wisdom interview series.